Northern White Sand mine, North Utica, Illinois. Aerial images taken with the assistance of the non-profit pilot collaborative LightHawk. (Ted Auch/FracTracker Alliance, June 2016)

Northern White Sand mine, North Utica, Illinois. Aerial images taken with the assistance of the non-profit pilot collaborative LightHawk. (Ted Auch/FracTracker Alliance, June 2016)

By Jamie Hwang and Tiffany Jeung

Mary Whipple’s day ends with throwing away bags of dust collected from her home in Waltham Township in LaSalle County, Illinois. “All that dust that I vacuum up in my bedroom every day,” she said. “You would not believe what I vacuum up from my carpet.”

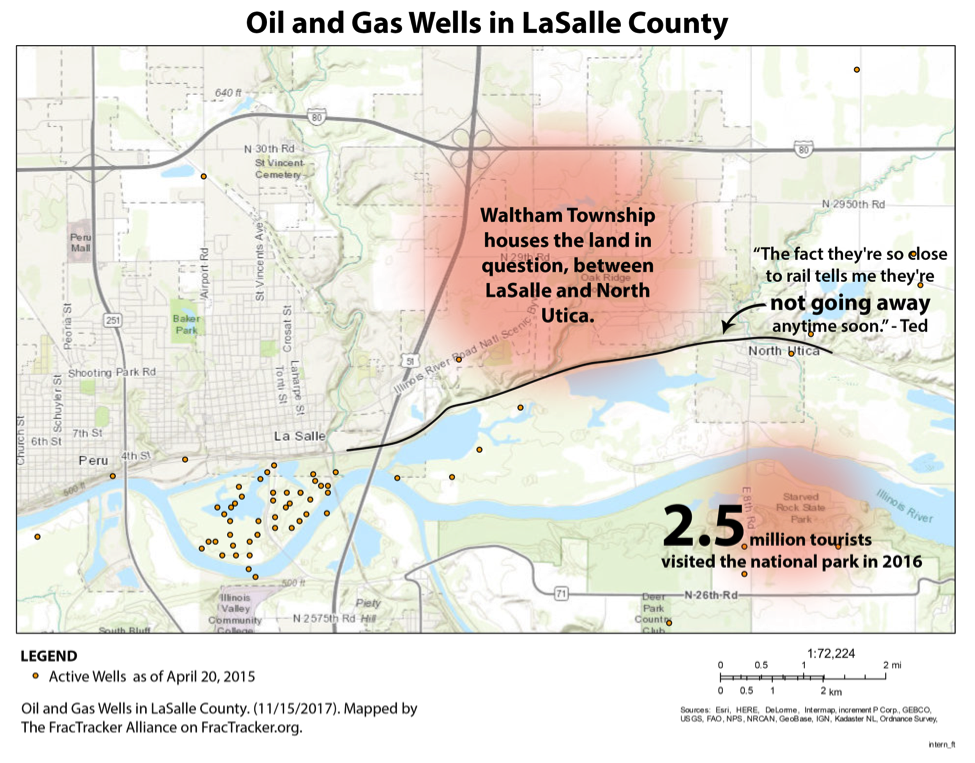

Since 2013, Mary and her husband Monty Whipple have fought for their community as plaintiffs in the ongoing lawsuit to stop a proposed sand mine that would be built close to their farm just north of Interstate 80 near the village of North Utica. The case is now back in the trial court, where defendants will be required to answer the complaint, and “discovery” will begin. The case will go forward in the Circuit Court in Bureau County, Illinois.

Mary Whipple, now 66, was born in LaSalle and lived in LaSalle County her whole life. Her parents, Richard and Irene Dittmar, also lived there all their lives, and Monty’s family resided on their nearby farm for generations as well. They’re fighting for their community and their legacy.

The story began when the North Utica Village Board gave a permit to Aramoni LLC, a division of the investment firm Woodland Path in Oak Brook allowing a sand mine to take over property previously intended for commercial development. The land is very close to the homes of people living in Waltham Township, which immediately borders North Utica. Nobody expected a sand mine and Waltham residents will be directly affected by the sand mine activities.

“Living where we have been for many years, we’re very aware of what mining does,” Mary said. “Stripping riches off of the soil and the possible contaminations, truck traffic and hazards that go with mining? There’s a place for everything, and this isn’t the place to have it. That land is a God-given gift. You’re never going to be able to replace it.”

The lawsuit focuses on the prospective nuisance that will negatively affect the well-being and daily lives of the families — mostly farmers — living close to the site. Even though LaSalle County has many sand mines, none have been directly built on vast acres of prime farmland. The land had been sold, however, for commercial development.

Fracking (known as hydraulic fracturing) is an oil and gas extraction technique that involves breaking up rock underground to release oil and natural gas deposits by pumping liquids into wells at high pressures. The chemicals used in the process and the risk of groundwater contamination are major concerns raised by fracking, according to Ted Auch at the FracTracker Alliance, an organization that makes energy-related data, especially on oil and gas issues, more accessible and actionable for the public. Auch is the Great Lakes Program Coordinator of the FracTracker Alliance and teaches geochemistry and soil science at Cleveland State University, in Cleveland. He focuses his work on environmental justice issues from watershed resilience to sand mining.

The fracking mixture to break the rock contains water and sand, as well as other chemicals. North Utica’s sand, with its consistent, even texture, meets the requirements to hold open rock fissures. With sand propping these human-made cracks open, the chemicals help oil or gas rise to the surface.

Fracking isn’t new, but it’s growing. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reports that, as of 2015, fracking produced two-thirds of natural gas in the U.S. Although fracking may be talked about as a “not-my-problem, not-my-town” issue, active fracking exists in 34 states. Given the quality of sand in LaSalle County — already known as the “sand capital of the world” by the Illinois Geographic Alliance – increased fracking means the targets on the back of rural citizens grow ever larger.

“I was struck by the scale, the size of the mines. The mines in LaSalle County are so much bigger than the mines I’ve seen in other states,” Auch said.

Why are people such as the Whipples fighting to keep sand mines away from their homes? Because frack sand mining comes with serious potential consequences, as Auch shows in his research.

“In LaSalle County, Illinois, they used to be able to see the stars,” he said. “And now, if you’re too close to these mines or floodlights, you can’t see the stars.”

Silica sand, a carcinogen that easily floats from mines to neighboring land, is linked to a higher risk of lung cancer, according to an infographic by the FracTracker Alliance, citing Mayo Clinic doctors. Already 30 to 50 times smaller than beach sand, silica dust can easily travel a half mile by air, and has been known to damage windshields as if the dust were sand paper.

The FracTracker Alliance links a higher risk of a host of other diseases to silica as well, from tuberculosis to lupus. Rick Coleman, another plaintiff who lives close to the prospective mine, has a 26-year-old daughter with a heart condition. The Coleman’s family physician put it plainly: the day that sand mine opens, they can no longer live in their house, he said.

High volumes of water consumption and contamination threaten communities as well. A nearby mine’s permit in North Utica Township allowed use of 1.25 million gallons of water per day, and a further study of the water table shows that another mine may strain local water sources.

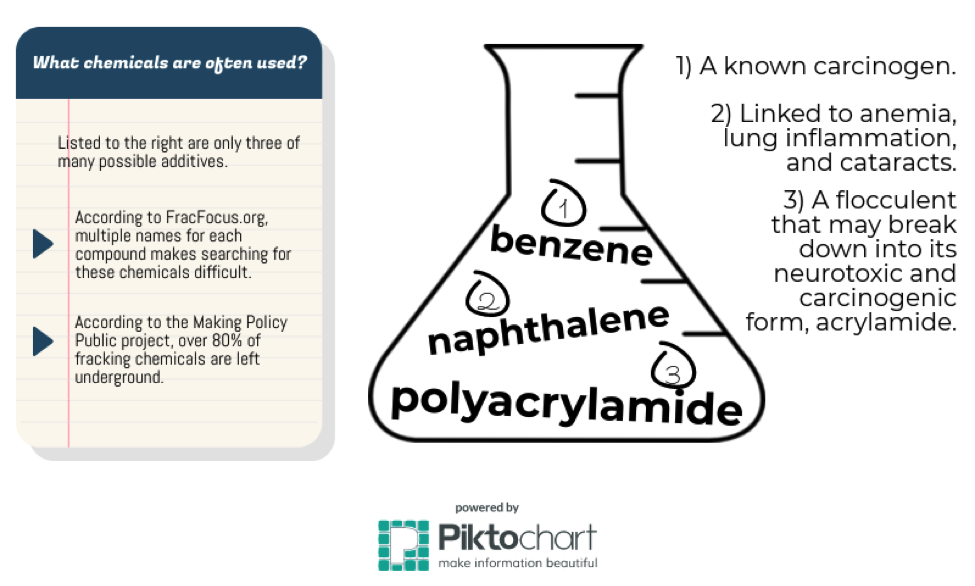

Carcinogens and neurotoxins are part of the chemical cocktail pumped into the ground in the fracking process. Damascus Citizens for Sustainability, based in New York, reports on the organization’s website that chemicals such as polyacrylamide, a flocculant used to clean sand, could break down to its more toxic form, acrylamide. “They definitely have some pretty nasty properties to them – cancer-causing properties,” said Auch. According to the FracTracker Alliance, other chemicals such as arsenic and naphthalene (think mothballs) are already water-contamination culprits at other sand mining sites in the nation. Not only the quantity, but also the quality, of the farmers’ wells are at risk.

Those living near sand mines risk potential damage and loss of property value for their homes as well. “Time and again you hear from neighbors who have seen cracks develop in their ceilings, in load-bearing walls, in their foundations,” said Auch, who documented a case in Detroit of a man living right next to a sand mine. “His house is basically uninsurable.”

“They keep saying that sand mining is an industry,” Mary Whipple said. “Agriculture is our industry. We create jobs. Illinois’ top sources of income? Agriculture and tourism.” The Whipples and the other 11 plaintiffs make it clear that the mining industry has long established its presence. But the proposed sand mine in the current lawsuit will encroach on high-quality farmland and the 2.5 million people who visit Starved Rock State Park each year.

The plaintiffs found hope when attorney and Professor Nancy Loeb with the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law’s Environmental Advocacy Clinic agreed to take on the case to challenge the planned mine. Although their complaint was initially dismissed, an appeals court overturned that decision in March 2017 and the case will now go forward.

The legal controversy focuses on land rights. The North Utica Village Board authorized the permit for Aramoni LLC to mine the land. The swath of land between the towns of LaSalle and North Utica was “unincorporated,” which means the land was not a part of either jurisdiction. However, North Utica annexed the mine site, striking a deal to allow the mine to function while preventing mining trucks from entering downtown North Utica and forcing the truck traffic onto the rural farming area north of Interstate 80, according to court documents.

Attorneys representing Aramoni LLC and North Utica declined to comment because of the ongoing lawsuit. At the hearing to dismiss the plaintiffs’ complaint on July 9, 2015, Ronald Cope, representing Aramoni LLC, argued that the laws do, in fact, allow the company to have a mine on the proposed site.

As cited in the transcript of proceedings of the hearing, Cope said, “So [the plaintiffs] have a burden of showing there is something unique about their area that is different than all the rest of the A-1 agricultural district, and there is something perhaps unique about this sand mine in its relationship to this unique area, whatever it is. And it’s not enough to allege that you live there or that you personally are going to be affected, because that’s true of every place.”

At the hearing, Cope was dismissive of the prospective nuisance presented by the plaintiffs, saying that chemicals, truck traffic and other factors in question all apply to any sand mine. He said, “There might be — there may be a discharge of harmful chemicals. Well, they use chemicals to some degree in the mining process, but that’s true of every mine. So what? Someone is going to testify in court that the mines use chemicals? And then what? No more mines?” The court of appeals rejected that argument and stated that the mining operations can amount to a nuisance, and plaintiffs are entitled to prove their claims.

Nancy Loeb, who represented the plaintiffs at the hearing, continues to fight for the residents of Waltham Township, to prevent the prospective nuisance such as blasting noises, bright lights and harmful chemicals that will negatively affect the residents living in close proximity to the mine.

“The way the contract works, the effects [of the mine] are pushed off to people who can’t vote in [North] Utica,” Loeb said. “No activities in this agreement will be considered nuisance [under the mining permit granted by North Utica]. Blasting noise, trucks and bright lights can go on 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they wouldn’t be considered nuisance.”

A lack of data also makes sand mining difficult to fight. Without data on mining sites before operations begin, residents of rural areas like LaSalle County have trouble proving the full impact of mining, from water use to waste disposal. The proprietary nature of mining means that companies aren’t willing to share data either. In an Ohio mining operation, when Auch and his team crunched the numbers, 25 percent of the water used couldn’t be accounted for. “How much [water] do they really need to process [the sand]? We’ve had a hard time figuring it out,” Auch said.

But plaintiffs such as Mary Whipple will continue to stand up for their town because they believe it’s the right thing to do. “This is an Illinois problem,” she said. “It’s everybody’s problem.”

While it’s easy to live far away and brush this off, more people should understand what’s happening with sand mines, not only in rural Illinois but also in other parts of the Midwest, Mary Whipple said. Citizens living farther from mines can make a difference too.

“If someone has a 401(k) or if they’re a member of an institutional union…make sure your investments align with your beliefs,” Auch said. “Money talks. And these companies are listening more and more to their investors.”

The farmers of Waltham Township will continue the fight to protect their community and hopes to succeed not only for themselves, but also for future generations, Mary Whipple said.

“This is our heritage,” she said. “I want to know that my grandson can have this one day.”