Judy Hogan, 81, is an environmental activist and author. (Photos by Emma Tobin/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Judy Hogan, 81, is an environmental activist and author. (Photos by Emma Tobin/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Judy Hogan is an 81-year-old environmental activist, writer, and teacher. Over the past few decades, she has fought a myriad of different environmental justice issues affecting her community in Chatham County, N.C. Right now, she is leading an effort against Duke Energy dumping and incinerating coal ash in her town. She publishes books and poetry and teaches writing classes twice a week as well.

This series is accompanied by selected poems from Hogan’s most recently published book, called “Shadows,” which is autobiographical about her daily life. I took a more free-form, artistic approach with this caption style because I want Judy Hogan to speak for herself:

“For me it’s shadows. Every day I walk across

the dam, I watch for my shadow marching

below me, down the hill, and some days,

when the wind is still, even across the water

and up the hill at the other end of the earthen

dam that creates Jordan Lake. In the painting

there is one small human figure surrounded

by rushing water, darkly threatening clouds,

with only a small window of blue that could

be sky but is probably water. That little

shadow is very persistent as she trudges

along. Even in a wind, she doesn’t hesitate,

pulls her hood up to protect her neck and

ears. A step at a time a great distance can

prove possible. But, oh for the courage

to believe in that shadow. I like to think

that when I’m gone, and even if storm clouds

dominate, and water boils and foams, and

wind is cruel and relentless, that my shadow–

all that is left of me and whatever words

on paper survive my death–will keep on

walking with firm steps, seeing more than

I can see now, accepting storms, even

lightning, but refusing to be dismissed,

ignored, or turned aside–something eternal

or stubborn, or so part of the nature of

things that it simply won’t let go.”

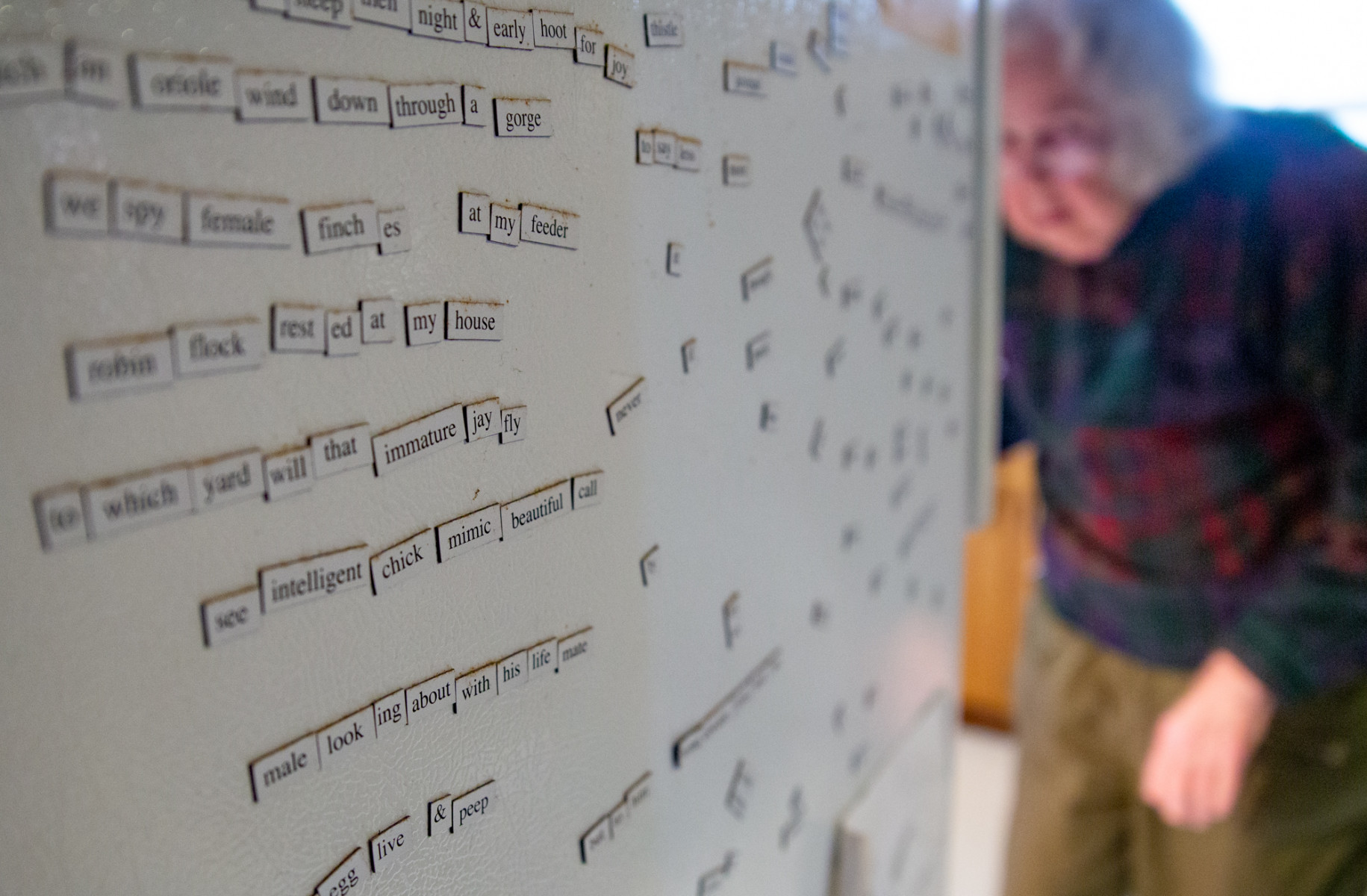

“How to tell it? I have a new friend

in the midst of my aging, when new

friends are rare. She’s a bird-watcher.

I’m a people-watcher. What I learn,

I scarcely know until I put it in my

books. Some mistrust other people

first and foremost. I attend to them

with my mind open. She talked to

my dog, and Wag listened. Wag is

tolerant now of other people but

skeptical, too. It takes time for her

to trust, but the bird-watcher turned

out to be a dog-whisperer and spoke

Wag’s language, baffling to me. Mind

over matter maybe. Wag would stop,

hesitate, and then touch her nose to

the outstretched hand. Me she pulled

in, too, to tell of the sixteen eagle

nests around our Jordan Lake. I

asked how they would have fared

during our hurricane. She said they

have favorite places to hunker down

during storms, but we had four days

of wind and rain, so she’s checking

on them. She watches for them to

fly by, way up there and catches

them in her camera the way she

caught Wag and me as we walked

toward her, both smiling, she says.”

“Erik Erikson said Ghandi found his

true identity when he was fifty. I

was seventy, still healthy, writing

and publishing books, teaching writers,

a small farmer with a flock of White

Rock hens, and a leader in my

community. At eighty, I take that

diversity of tasks for granted. I don’t

debate. It is a balancing act, and

my balance ability is distressed

by my age. Still, I rake and dig.

I hold onto tree branches and my

chain-link fence. I’ve said I’m

both Penelope and Odysseus. I

did have my once-in-a-lifetime

love–across the ocean, despite

the language barrier, and our

different lifestyles. We fought,

but we held on. He became one

of Homer’s shades, reduced to

shadows in the Underworld, but

still alive, still speaking and

foretelling the planet’s future if

we don’t attend to the signs. I’ll

be a shade, too, before too many

years have passed. Some of that

is beyond my control, and some

is up to me. The doctors urged

a cane four years ago, but I said

no. “I can’t farm with a cane.”

They said medicine, but I was

wary of the side-effects, the

medicine worse than the complaint.

My body heals while I sleep.

It puts me to sleep a lot. But my

aches and pains go away. I tell

them I have good telemeres.

They listen. The symptoms which

puzzled them have disappeared.

Eighty isn’t so bad if you accept

that your pace will be slower…

No, I’m not a shade yet, and life

still pulls surprises out of my

lucky grab bag. I can’t complain.”

“I was afraid my heart would rebel

and keep me from leading a workshop

on writing poetry. My friend had said

to rest more. I had things to do,

but I did stop to rest. Then six people

came to learn what I knew about

poetry. “What is a poem?” I asked.

They suggested it was condensed

words, that it was like a stream running

through the soul. I told them the

fourth grader’s understanding: “A poet

is someone who writes poetry, someone

who loves all living things.” I told

them about Homer’s Muse, about

the Old Testament prophets who

cried: “The Word of the Lord came

to me.” About how words could seem

to take off, and the deeper mind to

throw up words we weren’t expecting.

I mentioned Jacques Maritain’s hexis–

a gift we have in our unconscious

that we need to take care of and

listen to. If the poem starts in the

grocery store, make more room

in your life for the Muse. Then I

asked them to write a simple poem,

and they all did, even the librarian.

To my surprise, they all read their

new poems. They trusted me and

each other enough on very short

acquaintance. My heart behaved and

was quieted. Another unexpected gift.”

“Some see the world as a dangerous place.

I don’t. One says, “You see it as a safe place.”

I say, “No, but I see it differently. I know

there are dangers, but I’m focused on trying

to be in tune with the grain of the universe,

with the way it’s made. I follow my deep

intuition, even when it doesn’t make sense.

It makes me accident-unlikely. I may have

accidents, but usually they’re not as bad as

they could have been. So, yes, I had that flat

tire on Thursday, but it happened in my

front yard. I drove it across the road and

turned. When it was still bad, I pulled over

and stopped to look. I had a very flat right

front tire. Or I have car trouble as I pull into

a service station. I work toward peace

with my neighbors and fight for all of us

for cleaner air and water. They respect me

and protect me. I’ve never been harmed

by my neighbors, and I’ve often been

helped. You don’t need to worry about them

harming me.” I have a very different

orientation to the world. There are dangers

and evil people. If people are determined

to be my enemy, I stay away from them.

In the meantime, I try to have friendly

relations with everyone, if it’s possible. I’m

outspoken, and some people hate what I say

and can’t forgive me. One day I might be

harmed, but this way to live suits me.”

“Resting is hard for me. I have so much

I want to do before Shadows take me

from this life. Maybe

I don’t need to be so inactive. Can

I let go fear, slow myself down but

not stop, not let fear put its claws

into my soul, my trust that, if I pay

attention, all will be well.”

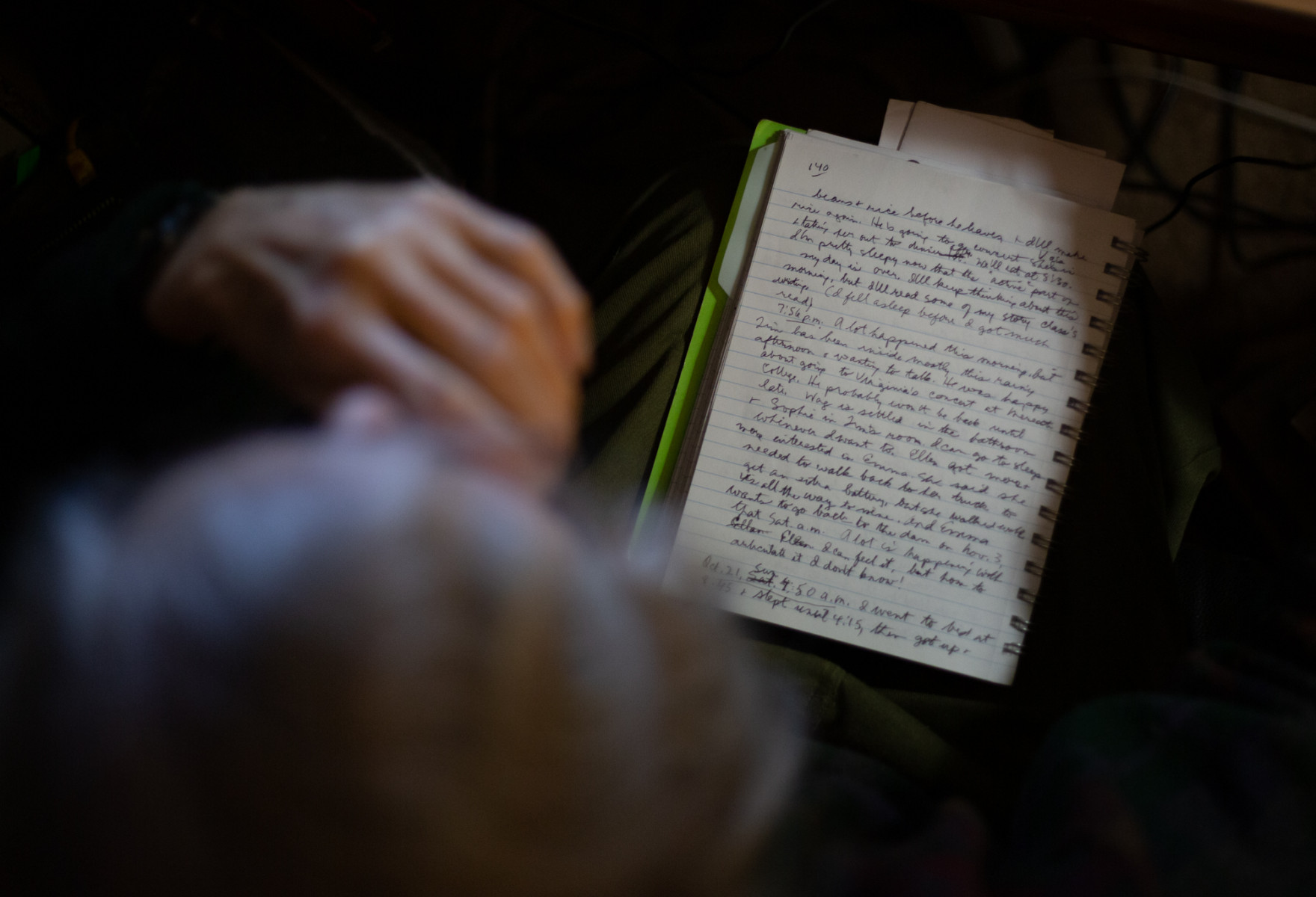

“Beginnings are hardest. In the morning

I sit up slowly, inch my way closer

to a place to hold on, rise carefully,

balance before I walk. I make sure I don’t

go too long without eating and sleep early.

As the day waxes, my confidence returns.

I remember what I need to, see to the hens,

make notes in my diary, in which I tell

the whole story. Sometimes I start to fall,

but I catch myself. At the dam I walk

steadily, don’t fear falling. Back at

home I’m warmer, shed layers, resume

morning tasks and rituals, with enough

energy for the day. By myself I see the

years of faithful work to leave my legacy

of stories and insights alive behind me.

Among others I see their discomfort.

They don’t look at me. They forget

my place in the line-up of poets. I make

them nervous. Why? Maybe because

I look into Death’s face and am not

afraid. How does one find that

particular courage? It arrives in time

to be useful in the last years, but I

realize I’ve practiced going my own way

most of my life, since age twenty-one,

to nearly eighty-one. Not dismissing

urgencies that would keep me whole

and safe, not denying love when it

defied logic. Those who hated me? I

stayed away, and generally, they did, too.

I sometimes lose things or forget them,

but I’ve never forgotten to safeguard

my soul and keep it whole, no matter

what my circumstances are.”

“Proust thought Time destroyed us,

those hidden memories our only

salvation. For me, Time allows

fulfillment, to come into my own,

to learn, to heal, and even to be

recognized and valued. There were

people who hated me, but they

didn’t stop me. My own body

slowed me down, reminded me

I had done well and to think of those

I love. I persuaded my friends

and my doctor to trust my way

of life, my faith in myself; to let

me continue my independent way.

My son and I learned to live

together. We lost some crops,

but harvested bushels of tomatoes.

I made spaghetti sauce and soup.

Now there are grapes to make

Muscadine jelly, pears to make

preserves. I do my work as a

writer, editor, teacher. I celebrate

Jaki, whom I first published

forty-five years ago. I will

teach poetry and story writing.

Like the moon’s slow, steady

increase of its light, I resume

my own life of work and love.”

“I slowed down, did easy work, nothing

strenuous. The hurricane left us to mop

up and dry out. Sun came back, the better

to see the devastation. Here, where we

escaped the worst, life was almost normal

despite rivers that flowed upstream, the

milk we couldn’t buy, the flooded roads

we couldn’t pass. I wanted more work.

I made a list I’m crossing off. Something

in me wants serious work, to tell some

story more than poetry tells or my

diary. A new book then about aging

and adapting. There is more to tell

than I have admitted so far. At eighty-one,

how many women tell what it’s like,

to lose the capabilities we always assumed,

to have gates closed, but the mind still

open, still able to articulate paradox

and justice, when everything in the human

being or in the state works easily and

smoothly together, each part doing its

own work? Mine has been to write, tell

my mind’s story. I’ve written many books,

but there is still more to tell. I will.”

“How do I describe my faithfulness to my

deepest knowledge, to what I see but

can’t easily reveal in words. I tried not

to be good as a child is good. I rebelled

against old formulas, trite words. I loved

Thoreau’s wisdom: “If I see someone

coming to do me good, I run for my life.”

I rejected that impulse to “do good.” Yet I

have always worked against evil when

I saw it blazing up in corporations, in

those fearful of rocking the boat, or who

were terrified to be seen as bad, as trouble-

makers. So I’ve been castigated, dismissed,

written off. It hasn’t been so bad. Some

tender hearts have loved me, and even

tough-spirited strangers have helped me

out. I have a few fans of my books. I

don’t need acclaim, but I do need to feel

loved and acknowledged by those I love

and trust, those who can see with clear

eyes who I am, what I care about. I’ve

been told many times that what I want

is impossible, will never happen. They

say life isn’t like that. You don’t get what

you wish for. In short, the power of evil

is too great. I don’t give up, however,

and then people love me. Things begin

to change. What my skeptics have

forgotten is the power of transformation

and what love can do when it’s unleashed,

when we see clearly, when other people’s

minds open like a book that wants to be

read. I can’t make that happen. I can’t

stop it. I can, however, give it my

gratitude and let it go to work.”

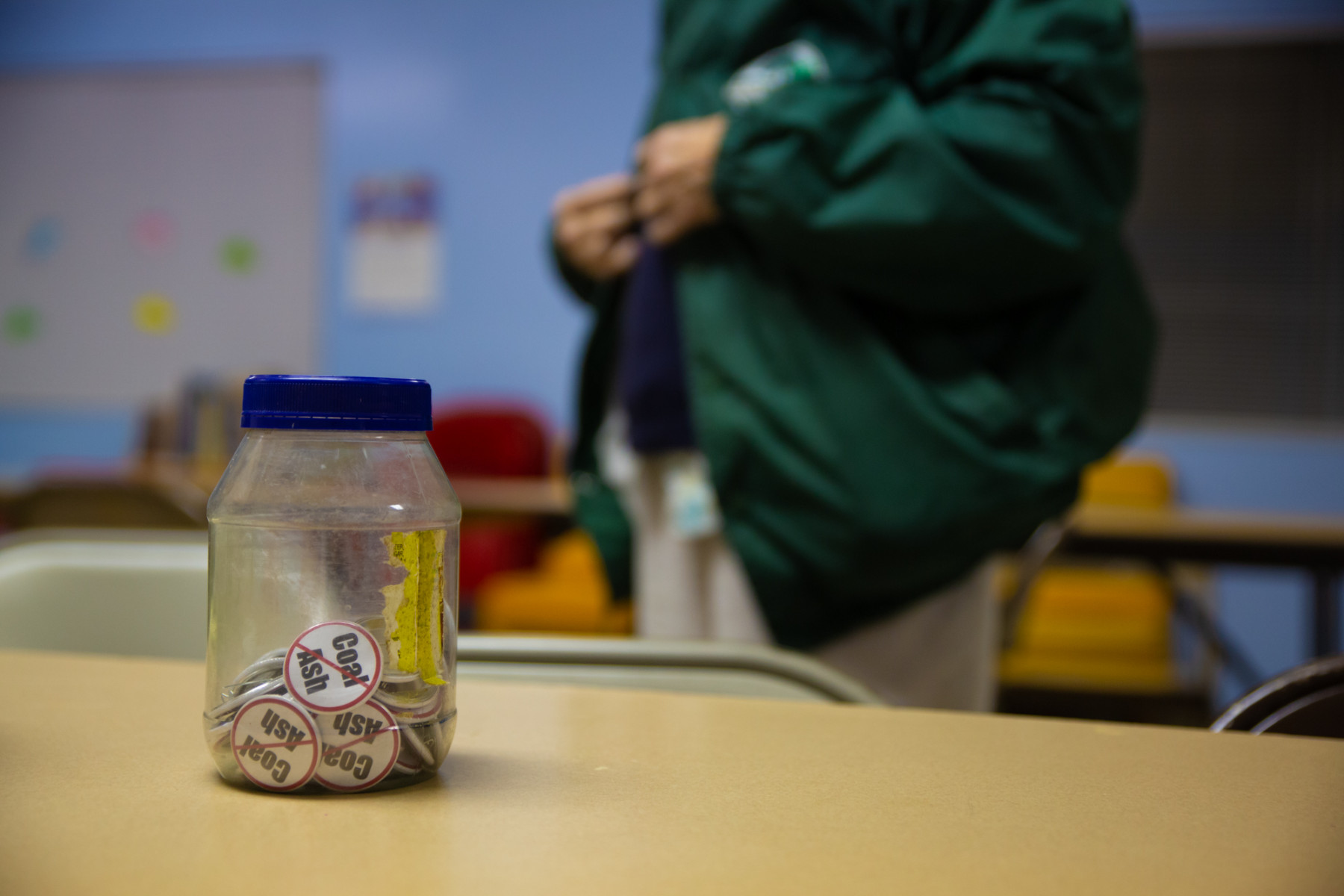

“Milosz helped me see, at age

eighty-one, that our worship of science

and technology, our allowing a dictator

to be elected president, is killing us off.

The big electricity corporation has brought

us a present we couldn’t refuse of seven

million tons of poison. They say they’ll stop

now. They’ve done enough damage. Instead,

they’ll burn the coal ash again and kill us

faster. No one stops them. People are

getting sick. They don’t want to fight

any more. They forget: when we fight, we

love each other. We can live with our

differences. Black, white, and Hispanic;

church-goers and non-church-goers.

Andrew says, “You’ve won a victory.

Have a victory party.” Rhonda says,

“You’re defying the doctors. I predict

you’ll have a stroke.” She’s angry at her

body’s weakness, and at me, for trusting

myself and challenging doctors, our techno-

masters in a sickening world. The human

body knows how to heal itself. Instead, they

give us pills and then more pills, and the

body then is truly sick, won’t fight any more.

Milosz lived under the Nazis, under Stalin.

He fought and he survived. I, too, am

fighting, and I, too, am surviving. Love

can conquer. Give it a try.”

“Even love has its misunderstandings.

Sometimes my son and I knock heads.

We’ve learned to let go when arguments

go nowhere. Everyone has her own world

view, her own life story, fears, and dread.

Agony is human, but so is joy. We watch

the exultant eagles join the circling vultures.

For one, it’s work-related, for another, it’s

ecstatic. When our hopes and desires

merge, worry disappears. When pain

returns, we are constrained to work free.

I write my troubles down, the better to let

them go. When they reappear, I’m

prepared. We all learn as fast as we can,

which means some more slowly than others.

A lot depends on our heritage and even

more on work we’ve already done to cope

when people hated us, when our loved ones

turned their faces away. The late years

lead to a homecoming or some call it a

home-going. We have some say-so. For

me, there are many rewards in this last

stage, which Erik Erikson called “Ego

integrity versus despair.” We find rewards

for our self-defense, our ability to listen

and give a helping hand. People we

scarcely knew turn up to help us. A young

woman wants to study me for clues to

living a benign life as a freedom-fighter.

Another woman in her middle years is

drawn to my relaxed humor. Most terrible

things draw our tears, but some that can

wrench us later make us laugh. My

doctor, as I eluded the medicines and

survived, calls me Trouble, but she’s

smiling. Another older woman says we’re

both eccentric, but a good eccentric. My

son is learning to protect garden spiders,

cherish poetry, and love my homemade bread.

I still walk without a cane, urged upon me five

years ago. Some work I’ve let go. I rest more,

but I do all I can do–gratefully. Look around:

I have students and friends. I’m cherished by

those I want to cherish me. I’m alive and writing

down what my last years are like. Already I

inherit that persistence I foresee in my shadow

after I’m gone. She’ll be okay.”