Darryl Fears is a Washington Post environmental reporter and 2020 Pulitzer Prize winner. (Photo illustration with photo courtesy Darryl Fears)

Darryl Fears is a Washington Post environmental reporter and 2020 Pulitzer Prize winner. (Photo illustration with photo courtesy Darryl Fears)

Darryl Fears has been a reporter at The Washington Post for 20 years and has been covering the environment for the last decade.

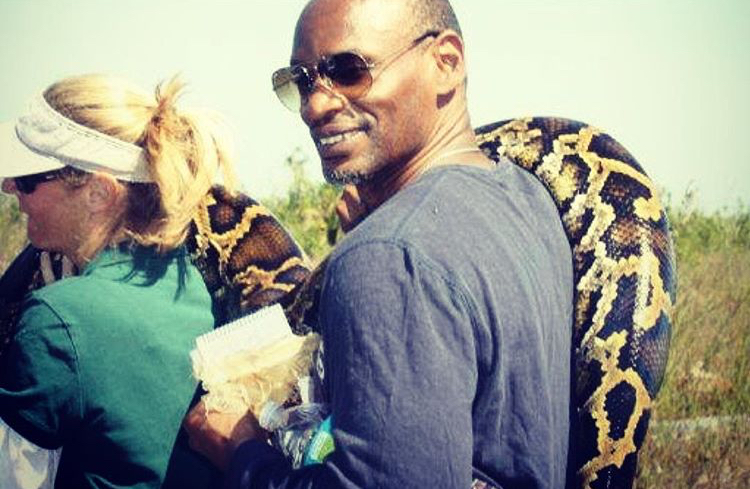

Born and raised in Tampa Bay, Florida, Fears attended a segregated school until sixth grade and studied art at St. Petersburg College. He fell in love with journalism once he joined the school’s newspaper but found that there weren’t many opportunities for a young African American man to become a reporter in Florida. In 1981, Fears began studying at Howard University where he majored in journalism and minored in both English and history.

Fears has covered wildlife, climate change, natural disasters, environmental racism, and so much more. He also has written about race, immigration, and the criminal justice system for The Washington Post, bringing extensive experience from his work at The Los Angeles Times, the Detroit Free Press and as the city hall bureau chief for The Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Recently, he and the team of climate journalists at The Washington Post won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting for the “2°C: Beyond the Limit” series, which breaks down how quickly the planet is warming and the resulting consequences. Fears’ story focuses specifically on Australia and how rising temperatures are threatening not only essential natural resources but an entire culture struggling to survive after centuries of persecution.

In a conversation in late July, Fears walked me through his experiences covering the environment and his Pulitzer Prize-winning work. He also gave insight on the decadeslong issue of excluding people of color in both the conservation movement and in newsrooms.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: When did you decide to pursue environmental journalism?

A: I came to the Post from the L.A. Times and came in as a general assignment reporter. And a year after that, I started writing about race and ethnicity and that evolved into a number of things from criminal justice to immigration…a colleague of mine, David Fahrenthold, who was covering the environment, decided that he wanted to cover Congress and David left a void on the desk.

I had expressed interest — just really sort of a passing interest — in covering the environment and an editor of mine remembered it and he thought I would be a good fit. I didn’t know at the time that I would be. And so I would say the long answer to your question is…I was assigned a position that I had a passing interest in. And I’ve been doing it now for 10 years because it has become one of the loves of my life.

Q: Was there a vocabulary or learning curve that you had to navigate when turning toward environmental journalism?

A: Yes. Scientists speak in an entirely different language from the rest of us. That was a huge learning curve to sort of understand how these research papers work, and what they were meant to say, and how they can inform journalism — and then how you had to sort of figure them (out), to read them, so that the average reader could understand that stuff. Because you look at the papers we write about and you look at the stories and it couldn’t be more different. The other challenge was getting some scientists to speak in plain language about what they were saying, because scientists speak to other scientists. They don’t necessarily speak to you and me.

Q: How did you overcome the challenge of taking scientific language and making it something absorbable for your audience?

A: Lots of time. So, it would take me a long time to read these studies. I would spend lunch hours and time after work understanding not just the summary and the conclusions of the studies, but also the guts of them, the explanations for the types of lab work and models they use to make their case. And all of that reading sort of went into forming questions. When I approached the scientists — this is the thing — that I would find the authors, of course, and not just one author, but two authors and I would talk to at least two authors for each study and then talk to a scientist who wasn’t involved in the study to sort of inform me about what actually the study is trying to say.

Some scientists are patient, some aren’t, but … you have to be willing to look really stupid to them because these are very smart people. But you’re trying to answer (the) questions you have. I really didn’t care that some scientists might think that I wasn’t a scientist or I wasn’t up to speed with certain things. I needed them to break down their information as much as they possibly could. Sometimes, the scientists were surprised at their answers and were surprised at how they were explaining the science. They began to see that there was another way that they could explain what they were trying to say. So, it was a bit of give and take. It was sort of symbiotic. I would say that (it) took at least six years before I was truly comfortable with reading studies. I think I’m much better at it now.

Q: How would you describe your own experiences as a journalist of color covering this particular beat?

A: When I started on the beat, obviously, I went to numerous engagements hosted by conservation groups and I was astonished to find that the sector, this field of conservation, was even whiter than my own industry, journalism, which is pretty white itself. But conservation was really white and I found that intriguing. And I think that two or three years in, I was like, I just can’t believe that. I can’t believe that African Americans and Latinos and Asian Americans aren’t interested in the environment.

So what’s happening here? And that led to my first story about diversity within green groups. And through writing that story, I learned a lot more about the environmental justice movement and how people in that movement had seen long before, that these groups weren’t just white, but they were racist. And they were sucking up (funding), and the foundations that basically gave them their marching orders and funded them also sort of left these groups without funds.

When I went to the Society of Environmental Journalists … you could almost count the number of Black environmental reporters on your hand — on one hand, not both. And, that is itself frustrating because white journalists just weren’t writing about these communities, and although there’s an explosion of interest in environmental journalism because of the environmental justice issues now — because of this racial reckoning we’re in — those stories are few and far between. I don’t recall any. I couldn’t find any story when I wrote about diversity in these green groups.

I couldn’t find that any white journalists had even thought to write that story. And that sort of tells you right there that they’re not engaged in these issues. They’re engaged in the way that these groups are engaged. It’s like, you know, we care more about the buffalo than about some area in some Black community or Latino community in Los Angeles that’s a heat zone, or that doesn’t have any green space, a park where children can play. So, those types of things, I think that that’s why Black journalists or Black environmental journalists are important because we see those things right away — those things that aren’t apparent to white journalists.

I don’t want to disparage all white environmentalists or conservationists or white journalists. It’s just, they have serious blind spots and they don’t see everything and they don’t write with urgency about some of the things that people of color care about. … Environmental justice is about to get some serious coverage. And I’m glad that I’m going to be a part of that.

Q: Can white journalists be effective storytellers now that this trend has been increasingly discussed and covered?

A: Yeah, I think that they can be. I think that white journalists are fully capable of telling the story once they are engaged. And I think that they are capable of empathy and understanding, and I think that they can write good stories when they ask the right questions and follow the right signs. So, I think that nowadays, that is possible. So if we’re talking about right now, I believe that they can, but they have to first be engaged. They have to first care. And I think that they are coming around to that, but slowly.

Q: You had mentioned the article you wrote in 2013 about the lack of diversity in the conservation movement. You recently wrote a story about the terrible history of the Sierra Club and many other organizations. How do you feel in this moment the conversation has progressed?

A: Bob Bullard said it best: It’s like baby steps. I think that the conversation right now around those stories that I wrote — the conversation around the story I wrote in 2013 is no different now than it was then. So these groups said that they would do more outreach and environmental justice work in 2013. The problem is they didn’t know how. They didn’t even know how to treat the employees. They hired Black employees to come in and do the work. And so I think that they need to look at that.

I think that the Sierra Club is drawing a straight line from its lack of diversity to its origins in white supremacy. And so, if that’s not enough to get you going, then nothing can. So, this is just a start. I know I’ve spoken to people who have no confidence that the Sierra Club will change. And the only way the Sierra Club can give them confidence is to change — a dramatic change. As Michael Brune, the executive director, said, “transformational change,” and that’s not just the Sierra Club. It’s the National Wildlife Federation, it’s The Nature Conservancy. It’s all these gigantic groups that get billions of dollars a year to do work that they do and cut Black and Brown people out of that. And so they have to learn that, one, their workforce needs to reflect the country, and two, that they have to learn how to do the work and give these people space to do the work. If they can’t, then they need to give the money to the groups that can.

Q: In 2016 you wrote a piece called “Racism twists and distorts everything.” I just want to read you a quick quote from that story, and pose the same question for you, now that we’re in 2020. You wrote, “Black Lives Matter was trying to force a difficult conversation that many Americans refused to have: How does racism drive inequality and fear, and how can we overcome that problem?”

A: Racism creates the other and, let’s face it, it was created by white people long ago in order to sort of collectivize people who weren’t white and make them inferior and make white people superior. And when you’re operating with that belief, and then the stereotypes that come with that belief — that these people are more prone to crime, and these people are more prone to things that are anti-society — you create fear.

Environmental racism is just under the entire umbrella of racism and you can go back to the way environmental racism essentially started with redlining — how white planners and the federal government, the federal housing administration and the public works administration, basically created Black communities and basically also created white communities and made one group a pariah and the other group safe. When you’re making one group, the white group, safe, you sort of set aside the other group — largely Black groups — for the most dangerous things. And so these Black communities were redlined around the worst areas of cities and suburbs — areas where there were power plants and waste facilities, incinerators and refineries.

When city planners planned or zoned areas, they zoned them in and around Black communities, or when they zoned housing areas for racial minorities, they zoned them in the worst places. And that’s how environmental racism came to be. How do you solve that problem? You recognize what happened, you recognize the zoning issues around this, and you have to tear it down. And I think that’s what environmental justice activists are doing.

Q: You had mentioned how it’s so important to have climate journalists of color as part of the solution. Why do you think environmental journalism is a beat that is predominantly covered by white journalists?

A: Um, every beat is predominantly covered by white journalists. So I think, once again, when you talk about a lack of diversity in the field of conservation, there is a parallel lack of diversity within media, and that’s all forms of media — that’s television, magazines, and newspapers. And often, when African Americans and Asian Americans are hired into these organizations, they’re siloed into particular beats and they’re not expected to cover certain things. And so, environmental science and environmentalism is just among those things.

Covering this issue…it’s not something that I would have seen for myself. And I think that years ago, a lot of African American journalists would not have seen this for themselves, but the editor who thought that I would do a good job at this because I’m really able to translate difficult information and make it readable for a lot of people, was a Black man. I don’t think that a white editor would have looked at me and said, ‘Hey, Darryl, you go handle that.’ It just doesn’t happen. So, just diversity in an editing position led to diversity in coverage of environmental issues at The Washington Post.

Q: I do want to talk about your story as part of the “2°C: Beyond the Limit” series. I was wondering if you could walk me through how you went about writing it.

A: The story in Australia came about because Australia happened to have a hotspot in it for 2°C…which is the so-called tipping point that the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) said is irreversible climate change. And so that area in Australia was the Tasman Sea. I was looking at the assignment and I was like, interesting, interesting, interesting…then I tied the (dying) seaweed to an environmental justice issue to involve the first peoples of Australia, which are so-called Aboriginal people of Australia — a white name provided to these people because white people thought that they were abnormal.

I began telling their story about how they were tied to the sea and their origin story about being in Australia (for) so long — 40,000 years — that they were able to walk to what is now an island. And also the story of their persecution. I used that as a narrative to drive the overall story — these people who were disenfranchised, who were trying to sort of reconnect to their culture and show Australia that they have a unique place in Australia’s culture, are losing their connection to the sea, which is their only way to demonstrate that they are a special people.

To me, that was just compelling. I just wasn’t prepared to discover all the horrible things that happened to the first people of Australia, the Palawa, as I later learned, and how they were wiped out essentially, by war and by persecution and basically bounties on their heads and (from) disease. And then the few that survived, the few that made it…white people began to lighten their skin color and take away their language and culture and were basically farmed out to white families as an attempt to breed the Black out of them so that they can be white, like other Australians. So I was like, ‘Oh man, what a story here!’ And I think that story, because of the way I told it, because I’m a Black journalist interested in the Black Diaspora, and how Aboriginals fit into that and how they fit into Australia’s history…it became one of the most important stories of the series.

Q: What advice would you give to people, during an unstable job market to say the least, who want to get into journalism and environmental journalism?

A: First of all, you need to be grounded in journalism. You first need to be a good researcher, a good reporter, and a good writer. You also have to be bold. You have to rely on your perspective and your point of view and sort of claim stories and make them different and tell a bigger story. And you have to be really, truly passionate about the environmental issues that are out there. I was fortunate enough to have this passion for it. The environment is the most important thing on the planet going right now. What’s happening with the environment will determine whether we survive as a species, as human beings. Have a passion for the work and be bold and represent.